InvenTech Enterprises

During my sophomore year of high school I joined a small engineering club and developed a device that brought us to Washington D.C. for the finals of a national competition. After a round of press coverage and a successful second year, I spearheaded the creation of a parent company for our team, coordinated what would eventually become Patent #US8820338B1, and learned more about engineering, entrepreneurship, and the many "soft" skills of leadership than I ever could have received from my coursework.

Looking back, this unexpected high school journey helped me break personal boundaries that made Tufts MAKE, the Maker Network, and my graduate Human Factors career possible. It also shaped my perspective on extracurricular education, the importance of "Learning by Making", and my ability to meaningfully contribute to others and my team.

Joining the team

In the mid-2000's a non-profit organization called the Junior Engineering Technical Society (JETS) promoted engineering and technology careers through programs and competitions for young students like the National Engineering Design Challenge (NEDC). Sponsored by the U.S. AbilityOne Program, the NEDC challenged teams of students to create new assistive technology devices that would improve the lives of people with disabilities in the workplace.

In late 2008 my high school's introductory science teacher, Mrs. Fennelly, announced that she would advise a new club to compete in the fourth annual NEDC with the help of two local engineers who were willing to donate their time and expertise. As a sophomore with a nascent interest in engineering and product design, I decided to join.

The first meeting was well-attended, but after seeing the competition's requirements and the time investment it would require, only 6 underclassmen and 1 senior returned for the second meeting. Feeling out of our league and already time-crunched by our advanced courses, my two friends and I (half the group) started to consider dropping out, which in a way felt like deciding whether the club would live or die. We agreed to attend just one more meeting.

Thankfully, that next meeting would change our feelings about the club dramatically.

The EATS

Identifying the problem and requirements

The first round of the competition asked us to find an individual with a problem in their workplace that could be solved through an assistive technology.

Two students on our team used wheelchairs, and they both agreed that storing and accessing their books and school materials was one of their most frustrating challenges. One student would typically ask his para-educator or another student to grab things out of the backpack hooked to the back of his chair, which was something he wished he could do independently.

Our team researched existing wheelchair storage solutions and found three general device categories:

- Side-hanging bags which were convenient to access but had low storage capacity

- Undercarriage bags which offered more capacity but were less accessible, particularly for people with certain conditions

- Regular backpacks which offered the most storage but were completely inaccessible without walking behind the chair or asking for help

After looking through discussion forum threads and talking with other students in our school who used wheelchairs, we found that the majority of students used the backpack method or wedged things awkwardly around their seat.

This seemed like a worthy problem to solve, so we created a list of requirements that we wanted our solution to incorporate:

- The device must:

- Be accessible from the side of the wheelchair

- Carry a wide variety of bags and purses

- Support the weight of a full backpack

- Not extend the width or height of the chair (to avoid getting stuck in doors or small passageways)

- The device should:

- Attach to a wide variety of wheelchairs (manual and electric)

- Use only a few, easy-to-replace components

- Be inexpensive to produce

- Easily detach from foldable chairs for storage

Creating a proof of concept

With our requirements in mind, the first thing we agreed on was to use the nearly-standardized handlebars as the mounting point for our device. Although the distance between handlebars varied from chair to chair, nearly every chair (including electric) had a pair of some kind of handlebars.

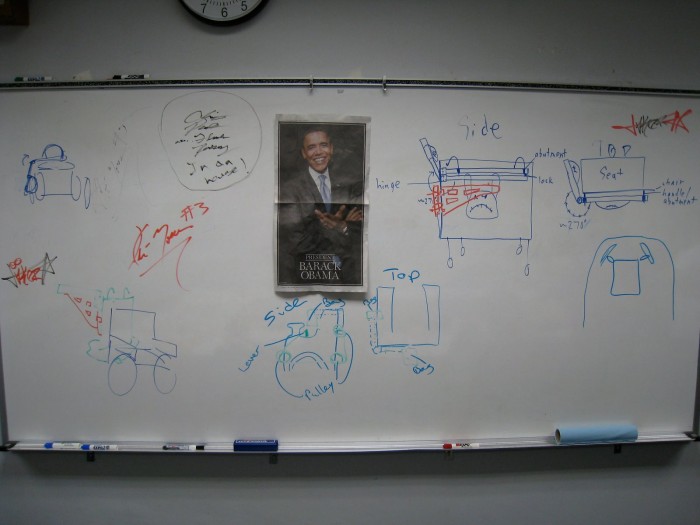

We also agreed that in order for the chair to be able to pass through doorways safely and maintain its center of gravity, the bag likely needed to be stored behind the chair when not in use. With those two constraints, we started sketching ideas.

First we considered a shower rod-like design that would allow a backpack to slide into place from the back of the chair to the user's side. A permanent bar protruding even slightly from the side of the chair could be uncomfortable and bump into doors, so we scrapped that idea. Another student suggested a vertical hook that would swing a bag to the side, but having a thick metal hook protruding from the top seemed dangerous.

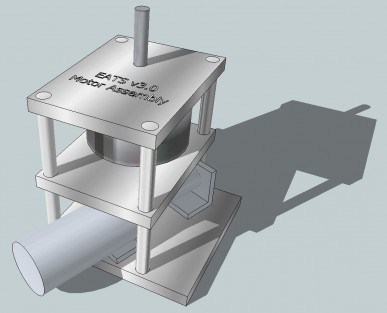

Our first design sketches, with my two-bar design at top-right.

Then I drew the design on the top-right of this image, with a door-like swinging design that could meet nearly all of our requirements. Two U-bolt hooks would connect the top bar to the handlebars, and a second bar carrying the backpack by its straps would rotate around its (potentially motorized) hinge to bring the backpack to the user's side. A heavy backpack mid-transit would put a lot of stress on the joint and require room around the user's back, but metal construction and a mechanical failsafe could mitigate those issues.

Rather than jumping straight into metal construction and high-torque motor mechanisms, our engineering advisors recommended that we start with a triangular wooden structure and a pullstring (drawn in orange). With the general approach agreed upon, we started to build a basic prototype out of duct tape and cardboard.

The beauty of this design dawned on us as we tested the proof of concept. Being able to carry any bag or box was useful not just at school, but in a wide variety of both workplace and recreational contexts. Our simple design combined the storage capacity of a regular backpack with the accessibility of a side-hanging bag without sacrificing day-to-day mobility.

We dubbed our prototype the Easy Access Transport System (EATS) and ordered some basic parts for our next build session. The club was finally starting to become fun.

Building a functional prototype

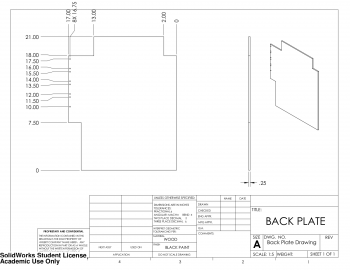

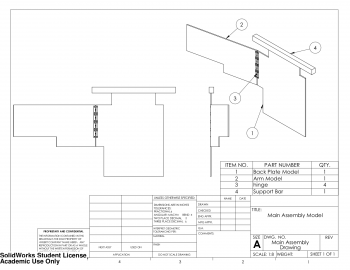

The next few weeks leading up to the submission deadline were a whirlwind. We visited our local medical equipment store to gather wheelchair measurements for a variety of brands and used that data to inform our prototype's dimensions. We were required to submit a CAD drawing of our prototype, so I requested an educational license of SolidWorks and used my experience with the program to create the drawings. To impress the judges I went one step further and taught myself how to use SketchUp to create an animation of the device's moving arm.

With the drawings finished we cut out our plywood pieces, connected them with a few cabinet hinges, wire-tied the assembly to a wheelchair's handlebars, strapped the bottom to the chair to keep it level, screwed on a hook to hang the backpack from, and attached a rope to let the user control the swinging arm.

The result was a crude but functional implementation of our idea that could carry the weight of a (mostly empty) backpack roughly 240 degrees around the side of the chair. The prototype worked well enough to include in a supplementary video submitted with our application.

Reaching the semifinals

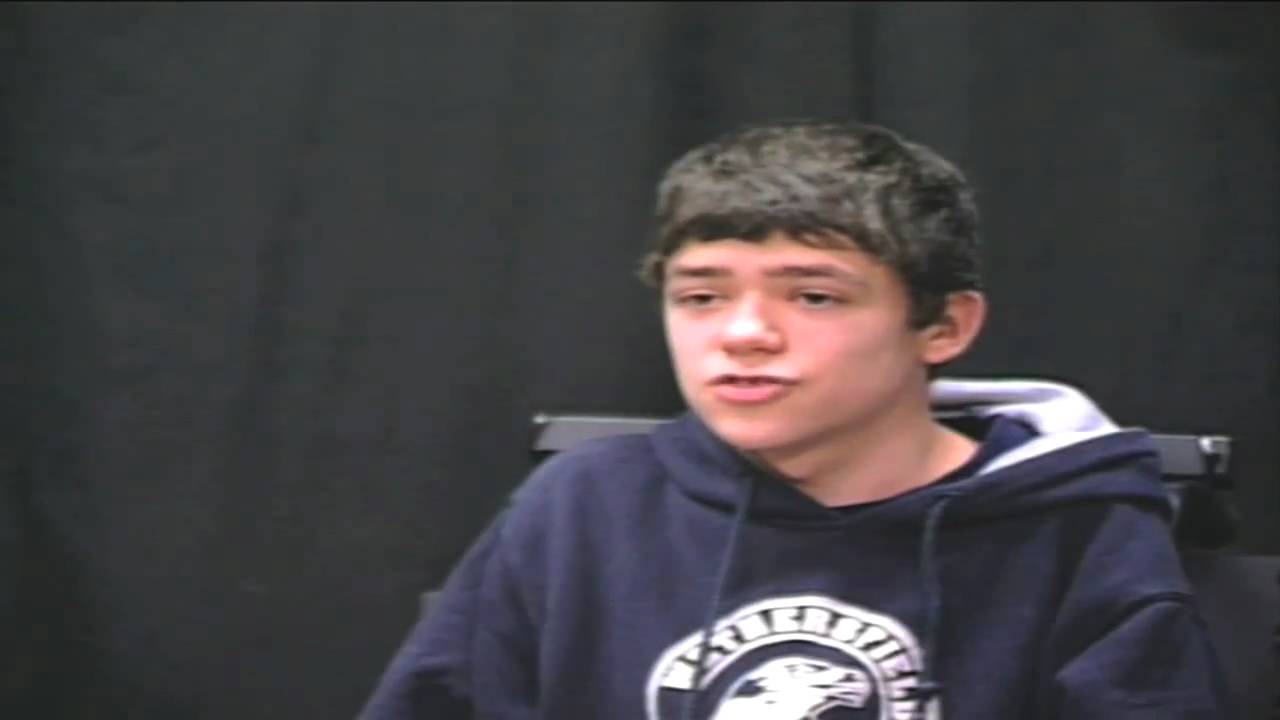

To our surprise, just before Christmas we were selected as one of 26 semifinalists from a pool of over 250 applicants from across the country. Our next challenge was to create a brief (under 6 minute) video demonstrating the prototype and our design process within 3 weeks, which meant working through our Christmas break.

Thankfully my good friend on the team was ready for this moment. He creatively came up with the idea of spoofing the "60 Minutes" show format with our own "6 Minutes" segment and got us permission to use our town's local TV studio, where he volunteered. I helped with the script, we filmed everything as a team, and then he whipped up a great video and green-screened Apple ad spoof that the judges clearly enjoyed watching.

We were chosen as one of 5 finalists to appear before the judges in Washington, D.C. the next month. As an underclassmen team that at one point had nearly disbanded, we were through the moon.

Preparing for the finals

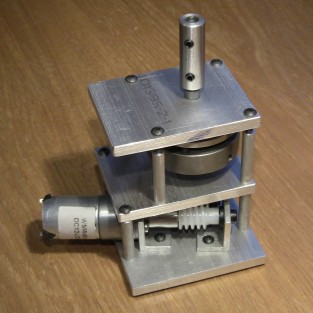

The judges gave us some feedback to prepare for the finals, including some skepticism about our claim that the device could adjust to multiple wheelchairs. We knew our second prototype was rough around the edges (wire ties aren't exactly a long-term solution) so one teammate and I committed to rebuilding it to address their feedback before we presented it at the finals.

We agreed that our next D.C.-worthy design needed to:

- Include an adjustment mechanism to demonstrate how it could attach to multiple chairs

- Be strong enough to carry the weight of a mostly-filled backpack

- Be more svelte

After seeing a few student athletes use crutches at school, I came up with the idea of using an adjustable crutch leg to make the U-bolts reach over 90% of the manual wheelchair handlebars that we measured. We also switched out the cabinet hinges with full door hinges and made sure that it was capable of swinging a full 270 degrees. Finally, we upgraded to 3-ply wood for additional strength and gave the whole thing a coat of black paint to match our demonstration chair.

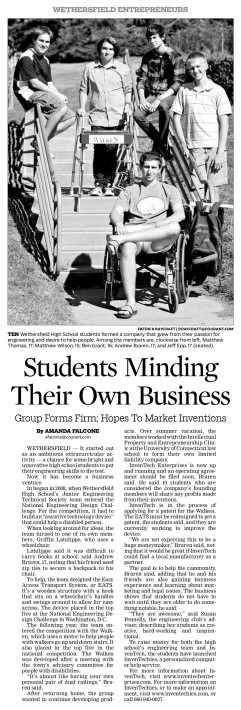

Local recognition

The weeks leading up to the finals were an interesting time. In addition to the pressure of presenting in front of a panel of expert judges in our nation's capital, our local TV news stations and papers started covering our team and asking for interviews. Our district's Board of Education invited us to be recognized and we were congratulated by our school principal over the intercom. As a quiet kid who had never done public speaking and disliked being on camera this was... an adjustment.

- Wethersfield Post on February 13th, 2009

- Wethersfield Life on April 9th, 2009

- Our local WFSB TV station's segment on the EATS

Prior to this coverage, Mrs. Fennelly and our volunteer engineers had the foresight to have a notary public sign our design documents just in case we decided to apply for a patent. This was prior to 2011's policy change from a first-to-invent to a first-to-file system.

Competing in D.C.

Our trip to D.C. was an influential experience. Seeing the work that other (equally nervous) teams had put into their projects was inspiring, and the guest speakers encouraged us to continue striving to help others as we returned to our regular lives.

Standing on that stage with my team felt like being in a pressure cooker at the time, but I now consider it to be a formative memory and moment in my career. Taking a chance and investing time into something other than my coursework had paid off in the form of town-wide accolades and the breaking of multiple personal boundaries that otherwise could have solidified to my detriment. Despite not placing in the top 3, making it to D.C. was a great honor and a personal accomplishment that helped me understand and acknowledge what I was capable of.

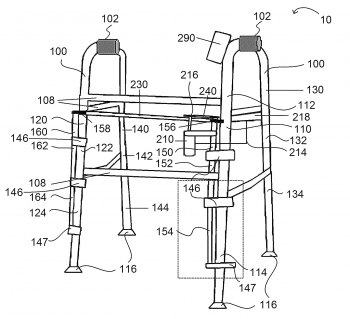

The Walken

Following the success of the EATS, a new group of students joined the club to create The Walken; a walker with adjustable front legs to allow users to more safely climb up stairs. The team once again qualified for the finals and our school's success had suddenly become a trend. I chose not to participate in The Walken's design process and was absent from the team that year, but was kept in the loop and occasionally provided suggestions.

Their semifinal video, JETS' finals video, and their article in the Hartford Courant are available online.

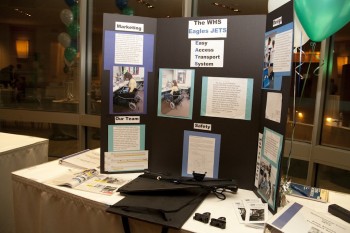

InvenTech Enterprises, LLC

Shortly after the team returned from D.C., Mrs. Fennelly suggested that I re-join to spearhead a new endeavor: turning the club into a company. She and the other advisors had an inkling that our prototypes could be patentable, and learning the process of forming a business could extend our extracurricular education into new directions.

In the ideal scenario, our company would patent and license the EATS and Walken designs to create a sustainable long-term source of funding for future NEDC teams. The company would also provide an avenue for students with a more entrepreneurial bent to contribute to our team and take our prototypes further than the NEDC required.

Mrs. Fennelly connected us to Geoffrey G. Dellenbaugh, PhD of the University of Connecticut School of Law's Intellectual Property and Entrepreneurship Law Clinic. His students began to investigate the likelihood of our designs receiving a patent, and he generously advised our team on the entire process of forming a Limited Liability Company in the state of Connecticut.

Our group held a meeting with all of our parents and advisors to propose the new venture, which I led. There was well-founded skepticism that everything would go according to plan and that members wouldn't leave after graduating, but we agreed that even if everything failed, we would have at least tried and learned from the experience.

That willingness to try was reason enough to start, and so we did. After many meetings to discuss logistics and create the necessary paperwork, InvenTech Enterprises, LLC was incorporated on August 2nd, 2010 with 10 founding members and the following mission statement:

We formed this company to support new and creative ideas, embolden youth to create change, and above all, make people smile. We strive to create new devices that make people's lives better. Simple as that. And by doing so, we hope to prove that young people don't have to wait until they "grow up" before they can change the world. Youth run, youth led, we are InvenTech, and we're creating a better tomorrow, today.

Getting a patent

Our first priority as a company was to pursue patents for our two designs. The UConn Law Clinic assisted greatly with the entire process, and coordinated with me to keep our teams in sync. Although the EATS was deemed to be too similar to existing patents to be patentable, The Walken's design seemed novel enough to warrant an attempt.

After many emails, meetings, and phone calls, we filed a provisional patent application for The Walken's design in December of 2010 and (without my involvement) were eventually granted Patent US8820338B1 on September 2nd, 2014 for a "Walker for improved stairway mobility".

Fundraising as InvenTechies

To raise funding for future NEDC prototypes, we started a Geek Squad-esque computer help service and helped roughly half a dozen clients with their technical issues. Our service had its own dedicated Google Voice number and town-wide advertising campaign, and we handed off phone call duties and dispatched as if we were our own sub-company. My grandpa was more than willing to be its first customer, and we helped our local TV station, teachers, school administrators, and Wethersfield residents as well.

More local recognition

A group of high school students starting their own assistive technology company after becoming two-time finalists in a national engineering competition made for a good story, so our local papers reached out to us again, including a front page color profile in the Wethersfield Life.

We were also invited to be honored guests at HARC's 60th Annual Meeting, where we received their Youth Community Services Award and spoke briefly about our devices and intent to help improve the lives of others.

By this point our group had become more comfortable with being interviewed, and it felt good to provide our town with a positive story about our school's club, company, and worthy cause.

Hartford Courant on September 28th, 2010

Wethersfield Life on October 10th, 2010

HARC Today's September 2011 issue

Improving the EATS

While juggling all of the the above, we also began working on a motorized, commercially-viable iteration of the EATS prototype with the help of our engineering advisors. We learned about gear ratios and torque, ordered parts from McMaster-Carr, created a new SketchUp model, and one advisor fabricated a working motorized block based on our design.

My hope was to demonstrate this prototype to potential manufacturers and possibly agree on a licensing agreement or at least impress them enough to support future NEDC teams, but the prototype was never completely finished.

Leaving InvenTech

As you might expect, a company run by high school students wasn't without its issues. In an attempt to be fair to everyone we intentionally kept our company's structure flat and didn't designate an ultimate decision-maker. Unsurprisingly, the result was an enormity of CC'd emails, a series of long and indecisive meetings, and an unspoken power struggle.

As my first semester of college approached it became clear that contributing from afar would be untenable, and likely hold me back from pursuing other opportunities (like TinkerTry and Tufts MAKE). I decided to leave the company with my other college-bound friends, and did so on June 15th, 2011.

The team's legacy

Even though our larger aspirations for InvenTech never panned out, the Wethersfield Design Team continued to grow and create increasingly functional devices that tangibly improved the lives of people with disabilities in the workplace.

In 2013 the team worked with CW Resources, a national organization that provides employment opportunities for people with disabilities, to test a device that made it easier for employees without fine motor control to create earplug chain boxes for the U.S. Defense Logistics Agency. The (formerly youngest) members of InvenTech led the team, and the Earplug Chain Fixture won 1st place in the AbilityOne Design Challenge that year.

The following year a new Wethersfield team won 1st again with The Path; a device that enabled CW employees to create stapled envelopes containing two chain necklaces without using their hands. The team had grown to 26 members that year, and exceeded 30 by 2016.

The accomplishments of these teams are of course their own, but I imagine that the lessons we learned as finalists and the town-wide awareness that our founding members generated were at least somewhat helpful to the ensuing generations and our school as a whole. The current Wethersfield team's technological skill, ingenuity, and legitimate helpfulness to others far exceeds what we had back in the day, and seeing their contributions makes me so glad that I decided to stick with the team back in 2009.

So much good has come from that one fork in the road.

My takeaways

Breaking out of my shell

With every step our team took from cardboard prototype to company, the awkward teenage boundaries I had set for myself became less and less defined. Prior to joining the team, the skills and abilities that had earned me A's in courses felt completely intangible and impractical. Without something "real" to direct them toward, I never felt like I could shape or influence something in my adult-driven world.

When the EATS took us to Washington and our local press started requesting interviews, my perspective began to shift. By the time InvenTech started, my sense of agency and confidence in my own abilities had nearly erased the timidity that had paralyzed me since middle school. Doing things outside of school was no longer an awkward waste of my time; it was absolutely the most valuable time of my high school career.

Looking back, I can trace a solid golden thread from my personal growth during EATS and InvenTech to the creation of Tufts MAKE, my own company, and eventually my graduate school education.

My life would be dramatically different had I not decided to join this team, and I'm forever grateful to it for so clearly pointing me toward my future.

The practical application of "hard" skills

From the real-world problem solving skills we practiced to the hours we spent crafting our company's Operating Agreement, our team put into practice a wide breadth of hard skills that we were only briefly exposed to through our coursework. Combining and applying the concepts I had learned from my Tech Ed, English, Science and Business classes into our projects established their importance in my brain, and influenced my eventual decision to pursue a trio of engineering, design, and business disciplines in college.

The effect of applied learning eventually became the "Learn by Making" mantra I advocated for via Tufts MAKE.

- Engineering

- Iterative prototyping design process

- Prototype documentation

- Woodworking and shop safety

- Windows and Mac computer troubleshooting

- Software

- Google SketchUp

- CAD (SolidWorks)

- Business

- LLC formation and fees

- Operating Agreements and power structure

- Small business taxes

- Patent law and the patent process

- Marketing and advertising campaigns

- Grant applications

- Writing

- Research reports

- Video scripts

- Clear and concise emails

Leadership, management, and "soft" skills

Turning our after-school team into a formal company immediately exposed the many soft skills that are needed to keep things running smoothly.

As I pulled together meetings and served as the primary point of contact for the UConn Law Clinic and local papers, my written and verbal communication skills improved greatly. Week after week I emailed the team to keep everyone in the loop and ensure that our deadlines were met, and eventually learned that while face-to-face communication trumped all other forms, unproductive meetings were exponentially worse in a team of 10 than tapping the right shoulders instead.

I also learned the difference between management and leadership first-hand, even in a flat company structure. Rather than forcibly delegate tasks, leadership meant aligning the interests and skills of each member with the work to be done, and wholeheartedly helping to fill in any gaps to ensure the team's success. Even without a formally designated "leader", they‘re identifiable by their actions and the way they reiterate and protect the company's vision.

Practicing these skills and learning about leadership through InvenTech would eventually shape the beginnings of Tufts MAKE; a second surprising journey that resulted from another step out of my comfort zone.